UNBELIEVABLE Steak Price Sparks Florida Outrage

How food prices quietly pressure your insurance bills

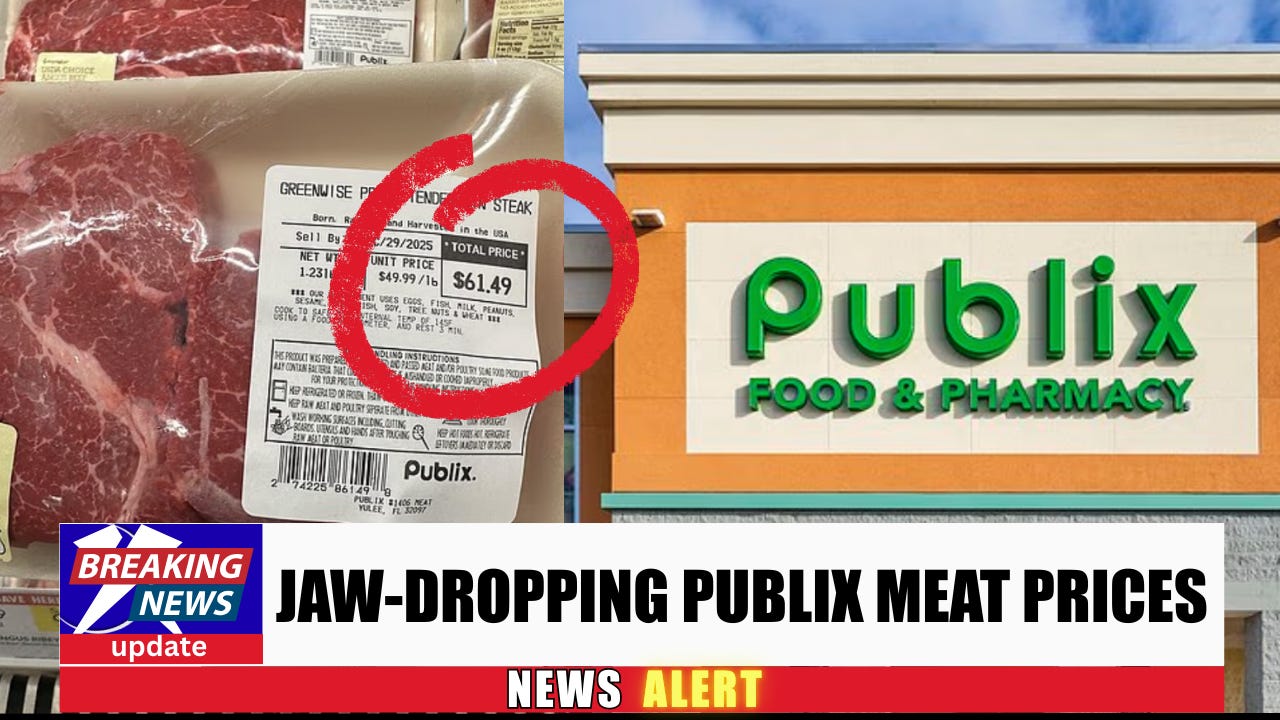

People usually think price gouging happens after hurricanes or disasters. But this time, the shock came from a refrigerated meat case, on an ordinary day, at Florida’s most trusted grocery store. A single package of tenderloin, sitting quietly on a shelf in Yulee, Florida, carried a price tag of sixty one dollars and forty nine cents, nearly fifty dollars per pound. No storm. No shortage announcement. Just business as usual. And for many shoppers, that was the moment something snapped.

Publix has spent decades cultivating an image of fairness, friendliness, and community. The subs, the smiles, the buy one get one deals, the feeling that this is a hometown store that looks out for you. Supporters argue that quality costs money, that beef prices are up everywhere, that labor, transportation, and insurance costs have all exploded. They point out that Publix pays employees better than many competitors and invests heavily in clean, well run stores. In that framing, higher prices are simply the unavoidable cost of doing business in modern America.

But critics see something else entirely. They see a company that has outlasted or outmaneuvered nearly every serious competitor in Florida, and now operates with very little fear of losing customers. When Kroger shut down its final Florida fulfillment centers, it quietly acknowledged defeat in a state where it once tried to gain a foothold. When smaller regional grocers folded or pulled back, Publix remained. Even national players struggle to match its footprint. With more than nine hundred stores across the state, the alternatives are limited, unevenly distributed, or locked behind memberships and longer drives.

That imbalance matters. Because when competition thins out, pricing power shifts. Shoppers online quickly compared the steak price to dining out. You can sit down at Outback Steakhouse, Texas Roadhouse, or LongHorn Steakhouse and get a full meal with sides and drinks for roughly half the price of that raw steak. Others pointed out that even premium grocers or warehouse clubs often offer better value per pound. Costco, with its membership model, wins on unit economics. Whole Foods offers specialty cuts and butcher counters. Trader Joe’s continues to expand, but its footprint remains tiny compared to Publix.

The deeper concern isn’t just food inflation. It’s what happens when a dominant player can undercut rivals long enough to push them out, then gradually raise prices once options disappear. Economists have warned for years that local or regional monopolies don’t look like classic monopolies on paper, but they behave like them in practice. The shelves stay stocked, the stores stay pleasant, but the checkout total keeps creeping higher, and customers have nowhere else to go.

This is where insurance quietly enters the picture, even if shoppers don’t realize it. Grocery prices don’t rise in a vacuum. Higher food costs drive up loss costs for insurers in multiple ways. Property insurers face higher replacement costs for inventory losses after fires, refrigeration failures, or power outages. Business interruption claims grow larger because restocking costs more. Workers compensation claims become more expensive as medical and living costs rise. Even auto and health insurers feel pressure when household budgets tighten and risk behaviors change. Those costs don’t stay with insurers. They flow back to policyholders as higher premiums.

Supporters of Publix would argue that insurance, utilities, and regulatory costs are exactly why prices must rise. They would say blaming one retailer ignores the broader inflationary environment and the reality that insurers themselves have sharply increased rates across Florida. And that argument has merit. Insurance costs have surged statewide, affecting everyone from homeowners to small businesses.

But critics respond that dominance changes the equation. When competition is weak, there is less pressure to absorb costs, streamline margins, or innovate pricing. The burden shifts almost entirely onto the consumer. And when millions of consumers pay more for basics like food, the ripple effects touch every insured risk in the economy.

What started as outrage over a single steak has turned into a larger question about power, pricing, and protection. Is this just inflation doing what inflation does, or is it a warning sign of what happens when convenience replaces competition? For now, Publix still fills parking lots, and many shoppers still swear by it. But each shocking receipt chips away at that goodwill. And if trust erodes far enough, the real cost won’t just be measured in dollars per pound, but in higher premiums, tighter budgets, and a growing sense that the system no longer works for the people paying into it.